Polar bears and penguins have become symbols of climate change due to the loss of their habitat. Global warming is threatening the ecosystems in the polar oceans. This is a serious problem because polar ecosystems play an important role in human nutrition and in absorbing carbon dioxide.

Nutrition

The polar oceans contain important resources for human nutrition. Many popular types of fish are caught in the polar oceans, and Antarctic krill oil is booming as a dietary supplement. This benefits both regional populations in the Arctic and also Europe and the rest of the world.

Carbon dioxide uptake

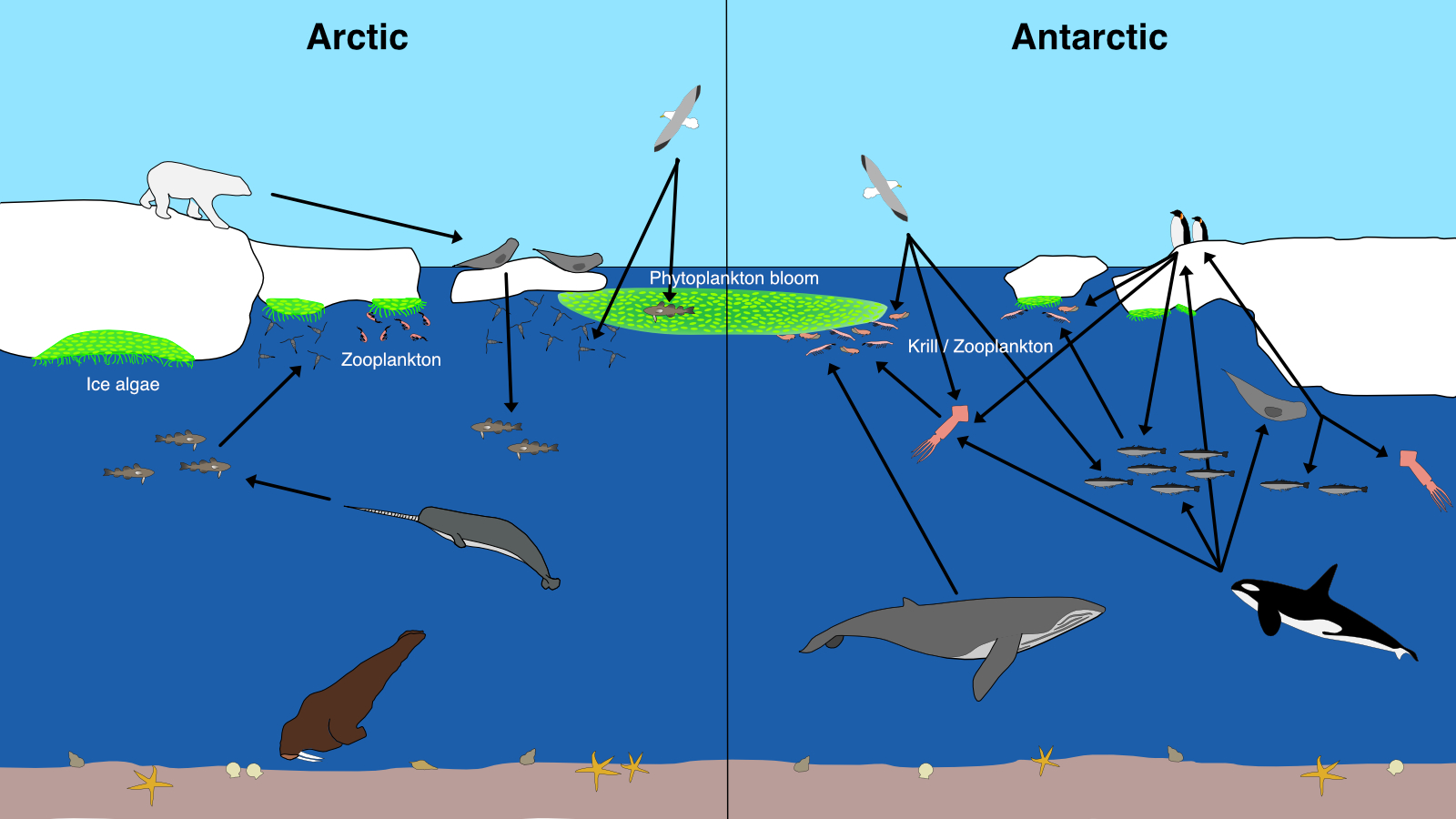

The polar oceans absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide and thus reduce the global concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Microalgae (phytoplankton) play a central role in carbon dioxide uptake. They use carbon dioxide for photosynthesis and in the process produce oxygen and biomass. As the algal biomass sinks, some of the carbon bound in this way is transported to great depths and thereby removed from the global cycle in the long term. This is known as the biological carbon pump. The algae are also the nutritional foundation of the marine ecosystem. The carbon bound in the algae can migrate through the entire oceanic food web, from small crustaceans and various fish species to marine mammals such as whales and seals. How much carbon dioxide can be absorbed through the biological carbon pump therefore depends on predator-prey relationships and also on the decomposition processes of dead organisms in the water and on the ocean floor. To date, these relationships and processes have only been rudimentarily researched.

How do ecosystems in the polar oceans function?

The ecosystems in the Arctic and Antarctic have adapted to the prevailing environmental conditions over millions of years. The polar regions are characterized by extremes of light and temperature. In winter, there is permanent darkness and extreme cold, and in summer, the sun never sets. Air temperatures can drop to minus 65 °C. However, organisms in the polar oceans encounter fairly constant living conditions. Seawater cannot get colder than minus 1.9 °C, because at that point sea ice forms. Polar animals and plants are adapted to the cold and light conditions, and despite the inhospitable environment, the polar oceans are teeming with life. However, even small changes in these stable living conditions can only be compensated for with difficulty by many organisms, sometimes not at all.

Sea ice plays an important role for many organisms as a food source, resting platform, shelter, or nursery. Every spring, when the sun reappears on the horizon and the days get longer, light begins to penetrate through the thick snow and ice cover to the underside of the ice, where ice algae begin to grow. Once the snow melts, enough light can penetrate through the ice to stimulate the growth of phytoplankton – very small, drifting, plant-like organisms that live in the water. This is followed by a bloom or population explosion of phytoplankton in the water. Algae and phytoplankton are food for higher organisms, the zooplankton – tiny marine animals such as small crustaceans and krill. The abundant food supply allows them to multiply at an astonishing rate. The protein- and fat-rich zooplankton is the food for a large number of animals at the top of the food chain, including penguins, fish, seals, and whales. In winter, sea ice provides protection. For example, Antarctic krill hibernate beneath the sea ice and use the ice algae as a food source. In this way, sea ice enables krill to survive until spring.

How are the ecosystems in the polar oceans changing?

Life in the polar seas is increasingly under pressure due to global warming. Polar marine plants and animals react much more sensitively to rising temperatures and other stress factors than marine species from temperate regions. Due to their special adaptation to constantly low environmental temperatures, polar organisms already show pronounced changes in their metabolic processes and reproduction rates in response to small temperature increases. Sensitive species shift their distribution if possible or die out, while more robust species expand. This can lead to lasting disruption of food webs.

As the sea ice shrinks in both polar regions, the habitat available to many species is reduced. At the same time, especially in the Arctic, feeding grounds shift poleward as the ice edge retreats. As a result, birds and mammals that previously hunted or fished at the ice edge have to travel longer distances. In addition, when distribution areas move poleward, the length of daylight changes, and with it the seasonal rhythm. This can disrupt the internal clock of organisms, which controls important processes such as food intake, reproduction, and fat storage. It is still largely uncertain what consequences the changes in day length or other environmental factors (e.g. changes in sea ice, the onset of phytoplankton blooms, changes in food quality and quantity) will have for polar organisms.

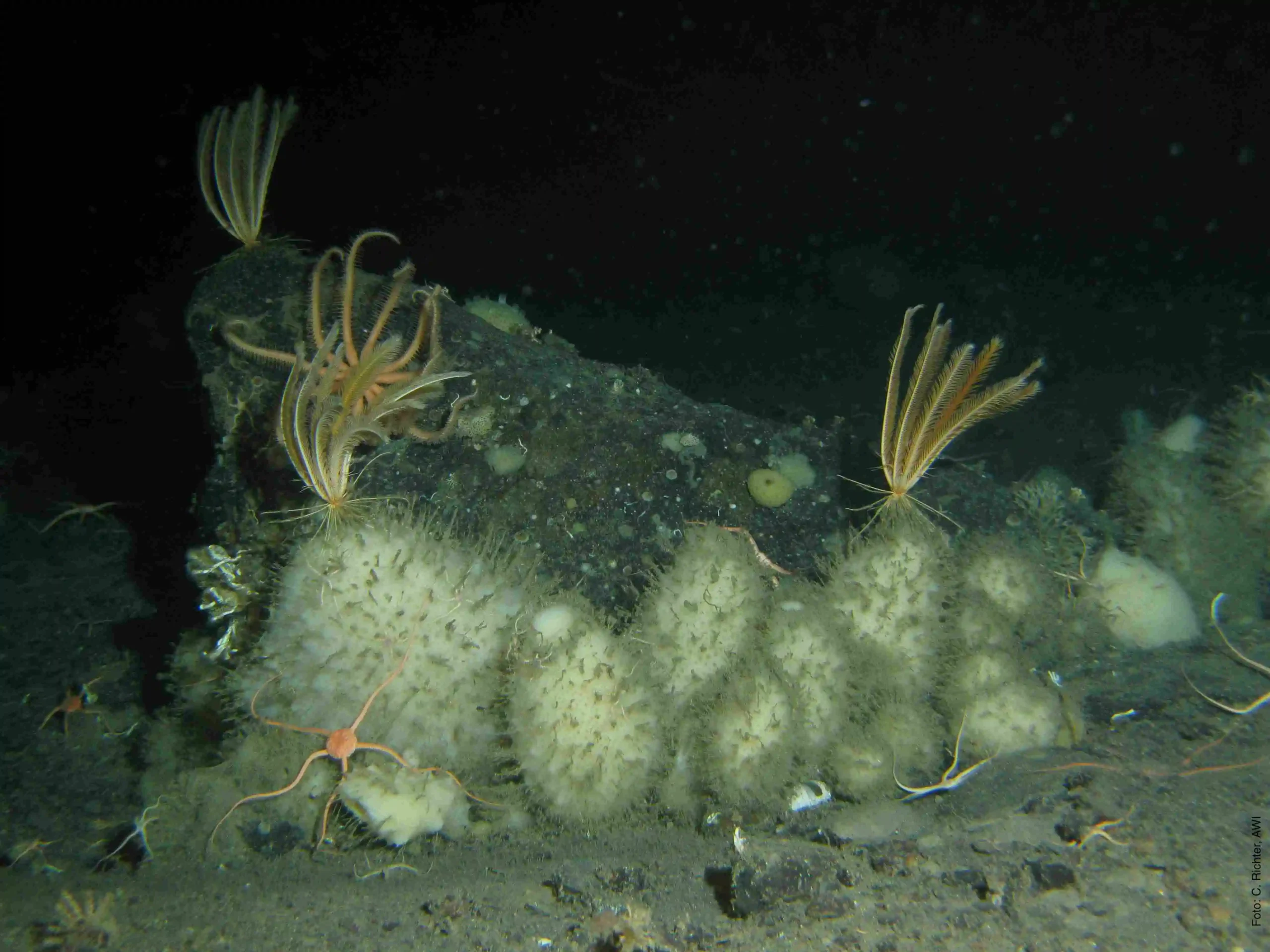

In addition, the increased uptake of carbon dioxide in the polar oceans leads to ocean acidification. This is particularly problematic for calcifying organisms and can significantly reduce the habitat of various plants and animals (e.g. crustose algae, mussels, snails, crabs), including key ecological species.

What is research working on?

So far, it is almost impossible to predict what consequences climate‑related environmental changes will have for ecosystems in the polar oceans. The impacts on the indigenous, regional, and global population are also uncertain. German polar research is focusing on the following questions:

How well can polar marine organisms adapt to the rapid environmental changes? Which processes are involved?

The diverse stress factors, such as rising temperatures and ocean acidification, lead to adaptation or avoidance reactions of the affected organisms. Mobile species are expected to shift their distribution areas poleward to cooler regions as far as possible. Such a regional shift has been observed in Antarctic krill with a simultaneous population decline. It was also observed in certain species of seabirds and marine mammals. Migrating species, such as plankton and fish species or killer whales, are entering the Arctic from boreal regions. Most polar marine species have low metabolic and growth rates and long life cycles and generation times. Often, they also have a low number of offspring. This can be disadvantageous when competing species from temperate regions move into the polar oceans. Long-term studies at representative sites are necessary to document shifts in distribution limits and seasonal migrations and to record changes in productivity and population status. The disappearance or migration of key species and the associated changes in the composition of communities and food webs can have a lasting impact on important ecosystem functions in the polar oceans.

Laboratory and field studies on the adaptability of key species to individual or multiple stressors and on resulting changes in food webs are necessary. These include investigations of the adaptive capacities of organisms, both physically and behaviorally. Studies on changes in the genetic diversity of populations and on gene regulation (epigenetics) are also necessary. Studies investigating the activation of genes under certain environmental conditions can also provide insights. Seasonal phenomena and rhythms need to be researched, as they shape the adaptation processes and strategies of many polar organisms. Furthermore, studies from the dark winter period are particularly rare and year-round observations are needed.

How and where does climate change endanger polar marine ecosystems with their special organisms, communities, and functions?

Habitats in the Arctic Ocean have already changed significantly. The Southern Ocean, especially in the region of the Antarctic Peninsula, is also severely affected by climate change. East Antarctica, including the Weddell Sea, may be at the beginning of a similarly large-scale change.

While the Arctic sea ice has been decreasing in extent and thickness for decades, a decline in sea ice in large parts of the Southern Ocean has only recently been observed. It is very important to analyze climate‑related changes from the outset in ecosystems that have so far been little influenced by climate change. These changes must be compared with known processes in the Arctic Ocean. Research into the communities in and under the sea ice of the polar oceans is necessary in order to better understand the food webs and to predict changes. An earlier onset of ice melt in the year could lead to temporal mismatches between food availability and the presence of consumers within the food web. Here, for example, the importance of ice algae for the reproductive success of algae-eating zooplankton must be determined.

How do changes in ecosystems affect usable goods and services for humans?

Ecosystem services are the “products” of ecosystems, such as food, or processes, such as the sequestration of excess carbon dioxide, which slow down climate change. A research focus is the impact of climate change on biodiversity, food webs, and productivity in the polar oceans, and how this affects the goods and ecosystem services used by humans. The adaptation strategies of polar marine organisms to the various stress factors must be recorded and understood. The ecosystem changes and their causes must be modeled using realistic approaches in order to enable reliable predictions of future developments under different climate scenarios.

Are there tipping points with irreversible consequences for these ecosystems?

To realistically assess the diverse impacts of climate change and identify climatic tipping points, the effects of multiple stressors in the polar oceans must be researched. The complexity of biological phenomena poses major challenges for the development of climate models. However, there are promising approaches in modeling to take key ecological processes into account.

Which species and ecosystem functions are suitable as indicators for the “state of health” of ecosystems in the polar oceans?

Indicator species can reflect changes in the condition of polar ecosystems. Already identified indicator species include Antarctic krill and penguin species in the Southern Ocean, and dominant copepods (Calanus species) and the polar bear in the Arctic. In addition to the microalgae at the base of the food web, these species are particularly sensitive to the consequences of warming and sea ice loss.

How does climate change affect food webs in the polar oceans, their productivity, and their role in the global carbon cycle?

The warming of the polar oceans is predicted to result in a shift from large unicellular diatoms to smaller phytoplankton (flagellates). The associated far-reaching consequences for productivity, interactions between key species in the food web, biogeochemical cycles, and ecosystem services have yet to be researched. It is also unknown whether and to what extent climate change will influence the biological pump and thus the organic particle flux to the seabed (marine snow). Will this change the composition of the bottom fauna, for example by replacing special filter-feeding communities (sponges, corals) in the Antarctic with opportunistic substrate feeders with lower species diversity? Understanding ecosystem changes is necessary both for research into biological responses to climate change and for science in the context of conservation measures.

How can robust future scenarios be developed from research insights in combination with modeling approaches?

Polar organisms react differently to climate change. It is very challenging to investigate the complex changes in the biotic communities. Field studies, laboratory analyses, and on-site experiments as well as ecosystem modeling are necessary to better understand the complexity and to identify key species and processes in the ecosystems. Based on this, realistic future scenarios can be developed for the biological sequestration of excess carbon – and the role of biodiversity in this – as well as for other ecosystem services. Such processes have so far been underrepresented in climate models. This also applies to interactions between marine and terrestrial ecosystems or polar and adjacent boreal ecosystems.